Introduction

Departures and Divisions: Variation in American Styles, 1900 – 1950, drawn almost entirely from TAM’s own collection, demonstrates how artists in early twentieth century America moved away from conservative European and American influences—notably the French impressionists and New York’s National Academy of Design—towards more distinctly American styles. This impetus was first led by Robert Henri, who trained in Paris in the early 1890s and who upon his return to Philadelphia began himself to teach, attracting a group of young artists (William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan) who were to remain an important part of his circle in future years.

In 1902, Henri became the most important instructor at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School of Art). His numerous students included George Bellows, Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Paul Manship, and Man Ray. He encouraged them to paint city scenes, a preoccupation that was to remain in American art through the 1940s and 1950s. In addition, following Henri’s example, many of the group, such as Bellows, Glackens, and Luks, painted portraits with highly saturated color and daring brushwork.

Museum. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Corydon Wagner, Sr.

Henri, however, was not the only influence that led to the development of new styles in early twentieth century America. Walt Kuhn and Arthur B. Davies were co-organizers of the 1913 Armory Show, which brought European modernism to the attention of artists and public alike. Inspired by, or as a reaction to the Armory Show, Americans such as Thomas Hart Benton, Arthur B. Davies, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Washington’s own Beulah Hyde and Vanessa Helder, developed their own personal styles. At the same time, American Scene painters, such as Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and Andrew Wyeth, tried to create a distinctly American style inspired largely by rural life, and widely seen as a rejection of abstraction.

By the 1930s these schools of American painting also included social realism and regionalism (known as American Scene collectively), as well as precisionism (applying cubist ideas to the depiction of architectural or industrial forms). There were also a growing variety of abstractionist movements, including the American Abstract Artists and the Park Avenue Cubists. These styles caught on across the country, including in the Northwest.

The Ashcan School and the Eight

Tacoma Art Museum. Museum purchase.

This portion of the exhibition includes works by some of the followers of Robert Henri, in particular William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan, who at the instigation of their teacher rejected the prettiness of nineteenth-century academicism. Henri began to encourage his students and friends to seek out American subject matter drawn from the less sophisticated aspects of New York City and its inhabitants. This is particularly visible in the work of Luks, Shinn, and Sloan, as seen here. Because of their espousal of gritty subject matter, Henri, Luks, Shinn, and Sloan became known as the Ashcan School. This loose-knit group coalesced into The Eight, who had their first and only exhibition at New York’s Macbeth Gallery in 1908, an exhibition which also included George Bellows, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast. Henri’s emphasis on painting aspects of the city hitherto thought of as ugly or unfit for art lasted well beyond the life of this group, and can be seen in works by other artists in this exhibition such as Jacob Lawrence and Kenjiro Nomura.

The Influence of the Armory Show

Organized mainly by Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn, under the auspices of The American Association of Artists and Sculptors, The International Exhibition of Modern Art (or the Armory Show) aimed to bring artists and the public examples of avant-garde European art, including fauvism and cubism. It astonished and even offended many Americans who were used to realism and academicism; one critic referred to Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase as “…an explosion in a shingle factory.” Despite the reception, the show had a significant influence on the development of several styles in America.

Art Museum. Gift of the Aloha Club in honor of Tacoma Art Museum’s 75th Anniversary.

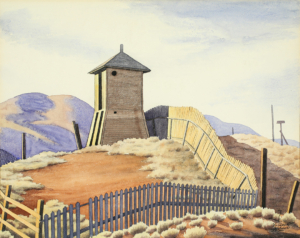

One of these styles is precisionism, in which artists came to use cubist-influenced geometries in their portrayal of industrial structures, as well as rural buildings such as barns (see Beulah Hyde and Vanessa Helder in this exhibition). The work of American modernists (such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Marguerite Zorach) was also heavily inspired by work on display at the Armory Show.

of the Aloha Club.

The American Scene

Two related realist styles developed in the 1930s and 1940s which concentrated on everyday city and rural life, and the land. These were regionalism and social realism. The social realists preferred depictions of city life, while regionalist painters more often concentrated on landscape and rural life, typically of the region where they lived. They were reacting against the dominant French styles such as late cubism, neo-classicism, and highly-colored modernist abstraction. Social realism and regionalism became virtually indistinguishable and, in the later 1930s and 1940s, they were the realist foil to the growing interest in abstraction.

Paintings and prints in this exhibition by the likes of Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood (known as the Regionalist triumvirate), as well as Howard Cook, Paul Landacre, and Thomas Nason, also demonstrate the American Scene aesthetic.

The Harlem Renaissance

Black artists are often absent from the art historical record due to discrimination against them for the color of their skin and systemic barriers to study, travel, and exhibition of their work to a broader public. Only recently has the wealth of talent possessed by many previously-unheralded African American artists begun to be recognized.

By the early twentieth century, avenues for African American artists to participate in the country’s artistic life gradually grew. One reason for this was the establishment in 1917 of the Rosenwald Fund by Julius Rosenwald, President of Sears, Roebuck & Co., which gave grants “for the well-being of mankind,” including to many artists of color. Another was the Harmon Foundation (established 1921) which, among many other things, circulated exhibitions with catalogues featuring works by African Americans around the country.

Another critical development was the Harlem Renaissance. In the 1920s and 1930s, Harlem, New York became a cultural mecca for Black creativity. At its broadest, the Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural coming together of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, and politics, the echoes of which live on today.

Influenced by these developments were such artists as Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, and Thelma Johnson Streat, among many others.

Associated American Artists

Associated American Artists (AAA) was an art gallery in New York City that, beginning in 1934, marketed affordable prints by major artists to the middle classes. This worked for everyone: the public could purchase prints for $5 each, plus an extra $2 if they wanted the art framed (all much more affordable than the prints offered by “high-end” galleries); while the artists, many of whom were impoverished because in the depth of the Great Depression their regular galleries were failing to sell their paintings, were guaranteed $200 for an edition.

The Influence of Mexico

In the 1920s, following the Mexican Revolution, the Mexican government began commissioning murals celebrating the country’s history and vision for the future. They included important figures as well as the everyday life and seasonal festivals of its various regions, interests that influenced every art form. Mexico’s foremost political print shop was the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphic Artists Workshop) organized in 1938. The GP attracted not only Mexican artists but an international group of printmakers who then carried the Mexican graphic style to other countries, notably the United States.

The powerful figurative style of muralists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco deeply influenced a host of American artists, particularly those who created public artworks under the US government’s New Deal art projects of the 1930s.

Abstractions

Abstraction was the “un-American” style that the American Scene realist artists struggled against, yet in the later 1940s the New York School of abstract painters became dominant. Jackson Pollock (whose teacher was Thomas Hart Benton), Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning all borrowed elements from European abstraction and the American Abstract Artists group of the 1930s, and developed abstract expressionism.

Parallel developments in the Northwest, by artists such as Mark Tobey and Milt Simons, provide a glimpse of how a different brand of abstraction became popular in the Northwest in the 1940s and 1950s.

Departures and Divisions: Variation in American Styles, 1900 – 1950 is now on view at Tacoma Art Museum through September 4, 2022. Explore the show on our website and on eMuseum.

Source: Tacoma Art Museum

Recent Comments